Reading Log, February 2007

I didn't plan it, but it turned out that a good deal of my reading this month revolved about WWII and the immediate post-war years. To keep my mind from being completely stuck in the 1940's, I also have a couple of Victorian era choices, and one futuristic novel. After hardly finishing any books in January (though I read a good deal), I finished seven in February. As I said earlier, I doubt I will be able to maintain this much reading all year, but it has been fun.

Dracula, by Bram Stoker--I listened to this as an audiobook from Librivox (I love those folks). In the end, I decided I didn't have much to say about it. Gothic horror isn't exactly my cup of tea, but at least now I can say I've read the book. If anyone asks. I don't want to give away any spoilers, but I thought the beginning was the very best part. In my opinion, the ending dragged on too long and was anticlimactic. I got a lot of crocheting done while I listened, however.

Lily's Crossing

by Patricia Reilly Giff--This was my easy children's lit book for the month. This one is set in the US during WWII and one of the characters is a European refugee.

The Secret by Eva Hoffman--I finished this book and I'm halfway through the autobiography. I can hear the author's "voice" in both books, and I will be looking for the other titles published by this author.

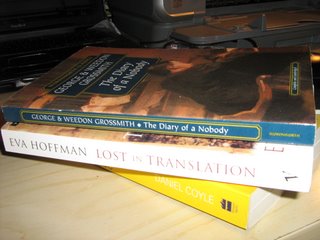

Lost in Translation by Eva Hoffman--This is the one I may have read before, but I have not encountered anything that is so familiar I am entirely convinced. I guess I'll have to take my husband's word for it. Much of this book takes place in post-war Poland.

Diary of a Nobody by George & Weedon Grossmith--This hilarious spoof on a Victorian middle-class working family has been a welcome counterpoint to the heavier reading I've been doing. I'm almost finished with this one, and I'll write more about it when I'm done.

W Pustyni i w puszczy by Henryk Sienkiewicz--I have made progress in my Polish book this month, although I'm only about 1/4 of the way through it. When I finish this, I'm going to watch a Polish film based on the book, and then choose a modern book to read, instead of 100-year-old literature. I think it will be more practical from the standpoint of improving my Polish, which is the main reason for doing this.

Turnabout Children by Mary McCracken--I've enjoyed Mary McCracken's stories about teaching children since I was about 11 years old, and this book was no exception.

Death at the Dolphin by Ngaio Marsh--I had a good time with this mystery, but when I finished it I realized I'm really not in the mood for mysteries. I will read more of her books (especially since I can check them out of the library in Krakow), but not for a while.

School Education by Charlotte Mason--A stimulating dose of educational philosophy every week, by one of the the most intelligent and widely-read women I've ever known. I'm reading and discussing this with the CM Series list.

The Literary Discipline by John Erskine--I finished another essay in this book entitled "The Cult of the Natural." Erskine's frank discussion about literature as an art is challenging. I'll include a quote at the end of this post.

Dawn to Decadence by Jacques Barzun--This is my year-long reading project and Barzun's unsentimental discussion of history, religion, art, and people continues to engage me. This very long book has a surprisingly conversational tone, without being at all "dumbed down." Unfortunately, to stay on schedule, I should be up to page 120, and I'm only on page 70. I will need to pick up the pace in March, but the reading is so dense it's hard to read much in one sitting.

Night by Elie Wiesel--Yes, the book just came in the mail yesterday. Yes, I read it already. I have to let it sink in a bit before writing about it, however.

The Time of Green Ginger by Armstrong King--I will finish this book today and probably write about it one more time. It is another post-WWII book, but its contemporary significance caught me off guard.

And now, after explaining that art is in some way an evaluation of life, Erskine says this:

For the special service of art is to make us live more intensely in the very life which art sifts and selects--in fact, the sifting has for its conscious purpose a more vivid realization of what we live through, and a novel or a play is successful, from the standpoint of imaginative literature, only in the degree to which we enter the work, become ourselves the hero, fall in love with the heroine, hate the villain. In this sense the dime novel and the melodrama, though carelessly branded by the theorist as bad art, are likely to be very good art indeed, and the over-reasoned story, though adorned with subtle reflection and refinements of diction, is in fact poor art, as the average person in his heart knows, for in such books the reflection upon life is paid for by a failure to represent what the reflection is about. If the author would only share with us the adventures that caused him to reflect, we could do our own reflecting upon them, but if he will not share the secret which inspires him, we do not care much what philosophizing he does.